I use new teaching methods to highlight people’s work that you may have not heard of elsewhere. For example, see here. To celebrate the Chinese New Year and the work of Rachel Tanur (1958-2002), an attorney and artist taken early by cancer, I examine one of her photographs to illustrate sociological concepts.

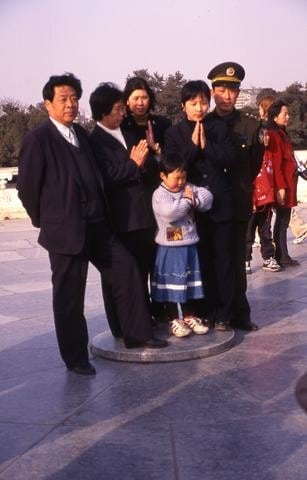

Since most human behavior is non-verbal, photography is a superb way to study it, and I use visual images to illustrate sociological concepts in teaching. Using the photographic work of Rachel Tanur is a prime example. Consider her photo, “Chinese Prayer.”

Key sociological institutions—the family, church (religion), and the state—leap from the still. In this mix of patriarchal relations of power and gender, religion as agent joins the audience. This is one of Tanur’s many projects that adds an illustrative dimension of meaning for sociological discourse.

First, this photograph captures the dynamics of family and gendered behavior. The men positioned, encapsulating the women, portray the historical patriarchal system of Chinese dynastic culture. Even as this is a dubious structure to be overthrown, they stand in a guarded posture of protection. At the same time, the women fulfill a powerful role as spiritual mediators, the function of “warrior priestess” (albeit within domicile constraint).[1] One notices their spiritual practice of prayer as action within the confines of an established cultural system. Curiously, the men are unattached to that same spiritual connection, seemingly as non-participants. Are they pausing to observe the outsider (photographer) at that moment, or does this portray their male constitution toward religious practice in general?

The child is in the center, notably the most protected position, and displays the most enthusiastic response in prayer. Why? Tanur’s art prompts the observer to ask sociological questions. Is it a childlike exuberance, an innocence to participate in the world’s cultural production, or is it a desire to demonstrate compliance toward authority placed over her? The daughter is imitating, to be sure. That she has acquired this behavioral knowledge via modeling indicates the process of socialization—learning and adopting the norms of a given culture—has already transpired. In this demonstrated collective behavior, how is religious ritual performative for each person in this photograph?[2] What demonstrates individual attestation or group compliance? Visual analysis is a key method to explore sociology in a fresh, unbounded way.

An element of visual sociology is a consideration of the recorder herself. Why did Ms. Tanur record what and how she did? What did she leave out of the frame? She left unclear to whom the women were praying. She also tightly framed the family as one unit, yet one wonders why she included non-associated others off to one side. One of them, scarcely noticeable, seems not of Chinese descent, facing away. This female (a Western foreigner?) joins the men in their non-participation of a religious practice which otherwise dominates the scene. With her back turned to the patriarchal way of the past (or present, some say), what does this woman’s posture represent for religion’s future in a globalized world, in which the distance between public squares of vastly different cultures is shrinking? Tanur demonstrates in her extensive travel that globalization—in its best form, cross-pollination—exposes historical roles for questioning. Photography is a method of representation and, as such, lures us to observe, to imagine, to assess, to question. Awareness brings possible change, and in this, Rachel Tanur and sociologists may share the same spirit.

[1] Jenny Hyun Chung Pak, Korean American Women: Stories of Acculturation and Changing Selves, Studies in Asian Americans: Reconceptualizing Culture, History & Politics, ed. Franklin Ng (New York: Routledge, 2006), 31-33, 40. Rosenlee, departing from the dominant view (e.g. Julia Kristeva, About Chinese Women), contests this historical dichotomy in her feminist interpretation of Confucianism. See Li-Hsiang Lisa Rosenlee, Confucianism and Women: A Philosophical Interpretation (New York: State University of New York Press, 2006), 69-70.

[2] Catherine Bell, “Acting Ritually: Evidence from the Social Life of Chinese Rites,” in The Blackwell Companion to Sociology of Religion, ed. Richard K. Fenn (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 383-84.